Last Monday morning, I watched Oprah Winfrey’s acceptance speech at the 75th Golden Globes ceremony and tears ran down my face. I’ve followed the #EverydaySexism project for a few years and watched with interest as the #MeToo movement evolved. Like many, I’ve had my own experiences of sexual harassment and assault to wrestle with in my (not yet published) work. As I listened to Oprah’s words and watched the rapturous response in the LA auditorium, the sense of relief that washed over me was overwhelming.

“For too long, women have not been heard or believed if they dared to speak their truth to the power of those men. But their time is up. Their time is up. Their time is up.”

Hope in dark times

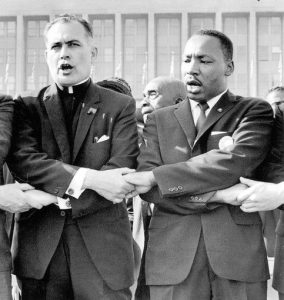

It is a powerful rallying cry to end sexist behaviour once and for all. #TimesUp immediately joined #MeToo as the watchwords for equality. Towards the end of her speech, Oprah mentions all the people she’s interviewed who have endured and overcome hard times and their singular ability to maintain hope for a brighter day. When she makes her promise of a new, brighter day is on the horizon, it is redolent of Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have A Dream’ and the joyful response in the room as everyone stands reinforces just how important hope is in complicated times.

It brought to mind my feelings at a recent storytelling event, ‘Do Justice: Voices of the Civil Rights Movement’, when the audience members were invited to link arms and sing together the words of the protest song:

“We shall overcome. We shall overcome.

Deep in my heart I do believe we shall overcome some day.”

We crossed arms and each others hands with one another in the same way that civil rights marchers linked arms, to demonstrate to each there and the world that their struggle was shared and to show their solidarity. The black dress code at the Golden Globes and the unanimous standing ovation in response to Oprah’s speech did the same for feminism and #MeToo. It all gives me hope that, one day, women might finally be listened to and taken seriously when we say we have not been treated as equals or given the respect or kindness that we deserve.

Wake-up call

I was jolted from my reverie of a warm rosy future by a text from a friend. She was alerting me to some unpleasant exchanges she’d seen in a message group our 10-year-old daughters are in. The dawning of that day that Oprah referred to in her speech suddenly seemed a long way off.

In a single moment, my friend’s text served to remind me that I am nowhere near diligent enough about monitoring my children’s online activity and, simultaneously, that I am so fortunate to have a friend who is. As soon as my girl came home from school, I would have to look at her phone to see what level of unpleasantness I needed to deal with. In the meantime, I had to shelve this dilemma and get on with my work.

Later, over lunch, a colleague told me how her child had come home from school, upset by something her teacher had said during a discussion on the week’s news. He had been responding to Oprah’s speech.

Old-school ideas

‘When I was young,’ he’d pontificated, ‘men went to work to earn money and that worked fine. Then there was feminism in the seventies and afterwards everything seemed to settle down a bit. Now it seems to have flared up again.’

It was the kind of thing – and I doubt I’m alone in this – that, as a teenager, I used to hear from my own Dad. I would argue long and hard with him any time he even hinted at inequality and, even though I didn’t always win, I ultimately dismissed such views as outdated and irrelevant; the boys I was friends with didn’t think like that. With hindsight, I can appreciate that not everyone feels fortunate enough to have those arguments, but I grew up in a home where healthy debate and argument didn’t lead to violent repercussions.

But this 13-year-old girl had been sitting in a classroom and these words had been uttered by her teacher. What were the chances that his remarks could lead to healthy debate? What thirteen-year-old girl would have the strength or confidence to stand up and ask, “Who did it work fine for?” for example. Or to question his use of the term “flare up” in reference to a human rights campaign? I had to wonder if he had passed this remark in the school staffroom, how many of his adult peers would have bothered to call him out on the kind of language he was using.

I’ve had similar disputes in the last year with two of my own siblings*. Disputes where I have had to pick them up on their misogynistic attitudes and where their response has been to dismiss my arguments as ‘political correctness gone mad’. When one of my brothers told me he thought the actresses who went to Harvey Weinstein’s room knew what they were doing and ‘a certain transaction’ would take place, the fury of my reaction coloured the air with shades of blue I don’t know the names of.

Safe place for debate

I feel safe enough to have rows like this with siblings, as I’m confident there’s little they can do to affect my income or my well-being on a day-to-day business. Could I say the same if these opinions came from a figure of authority? If they were uttered by the person who decides whether I have a job tomorrow? Or a home to rent? I call myself a feminist and I’m certainly more outspoken than most, but I’m not sure I can say, hand on heart, that I would.

Later on in the day, when I was doing the usual domestic admin job of checking and responding to emails about my kids’ extracurricular activities and lift-sharing, I read the message from another friend telling me that her 10-year-old daughter was having a rough time at school because a boy in her class was being particularly unkind to her; he’d told her that she had a monobrow and that she ought to wax her legs. The mother wanted to know if my little girl had had any similar experiences.

I pondered on it.

My daughter tells me at length what goes on at school. She tells me that there are a couple of boys at school who frequently do and say things to her and her friends that they find annoying. At the time of telling, I am usually most concerned with how she’s handled the situation and how she feels. I’m relieved to hear that she stands up for herself and others, and walks away from the situation. Nine times out of ten, when I ask her if she wants me to go into school, she’s not bothered and so we leave it.

I stopped pondering and asked my daughter to please show me the group chat on her phone.

What started off as a fairly innocuous chat between boys and girls rapidly deteriorated as a certain individual joined the chat. The further I scrolled, the more gob-smacked I was by what I was reading.

Bad versus toxic

For the record, I have no objection to swearing; I am completely with Stephen Fry on this, and anyone who knows me can bear witness to the fact that I relish using choice swearwords to add impact or humour of a story. But this boy’s rich repertoire of profanity is right up there with a Gangsta rapper for sexism and misogyny. And he’d probably take that as a compliment.

‘She’s a bitch’

‘Her friend’s a sket.’**

The girls call him out, ask him to stop swearing, but he continues.

‘I can call her a cunt if I like.’

A girl removes him from the chat.

A boy adds him back in and the rich language returns.

‘She’s my ho’

The girls try to ignore him and discuss something they’re doing at school, which he ridicules.

‘What you are doing is so gay.’

A girl removes him.

A boy adds him back in.

A girl gives some praise to one of the boys learning the guitar.

‘She gets wet just when she sees him.’

A girl removes him.

Another girl adds him back in much to the astonishment of my daughter and she later finds out that her brother had stolen her phone and adds the offending boy back in.

And then a picture of the Klu Klux Clan is posted to illustrate what he thinks of the girls removing him from the chat.

It’s just toxic.

But, horribly, what I read had a familiar ring to it. It was like a script of scenarios I hear played out in the real world time and again. The only difference being that here the verbal assault is written not spoken. The girls’ discomfort and repeated objections are evident; the silent collaboration of the other boys is visible. But this exchange was between children I know.

It gave me the biggest wake-up call I have had in a long time.

I’m a feminist and I thought I had brought my kids up to recognise prejudice and to do the right thing when they see someone being picked on or excluded. Through books and films, news stories and all the surrounding discussions about why people behave in certain ways and what the consequences might be, I thought I was doing enough.

Until now.

The right language

When Oprah said that #MeToo is not a story confined to the entertainment industry, it was a huge understatement. The broken culture that she describes affects all our politics and all our workplaces and, precisely because it’s in music, film, and entertainment, it’s in our homes and schools; of course it affects our children’s lives as much as our own.

What I’ve heard and read this week has seriously woken me up to the fact that activism means just that. It’s not passively watching others try to solve the problems and hoping. If I’m going to effect any real positive change, it means I really do have to keep my eyes and ears open and give my kids all the tools they need to work on it with me.

A few days ago, my daughter described a boy’s behaviour towards her and her friends as ‘just annoying’. She couldn’t express how or why it was annoying, because nobody had yet given her the language. Now she knows what the word misogyny means; she knows about #MeToo, and she knows to look out for sexist behaviour and language and to call it out for what it is.

Notes

* I’ve got six siblings; they don’t all have these views.

** sket was a new one on me, but thanks to the 10-year-old user of this term posting a screenshot of his favourite app (suggested usage: 17+), I now know that it’s a ‘scabby slut’.

Links

Oprah Winfrey’s 2018 Golden Globes speech

Time’s Up Movement to fight sexual inequality in the workplace

What parents can do to stop sexual harassment

Government guidelines on sexual harassment in school (December 2017)